The monetary regime in place in recent years shows signs of fatigue. The cost/benefit ratio of public policy has been reversed in recent quarters. It could accelerate the current correction of financial assets and reduce the valuation gap they previously enjoyed. Left on their own, markets are rediscovering the taste for risk.

In our last update, we argued that the series of events that took place in 2015 had a common thread: a long and painful process of normalisation of macro-financial conditions, that we called a “return to fundamentals”. There is no doubt that Q4 2015, along with the early days of 2016, point to a significant acceleration of this process. We believe we are seeing a regime shift in the fundamental framework.

This change is not only taking place in the monetary sphere but also in the real and public ones. Although the external symptoms are relatively easy to identify – falling oil price, collapse of emerging market currencies, growth downgrades, public tensions and heightened financial volatility – its inner workings are in our view largely underestimated. Nevertheless, they call for a fundamentally conservative attitude.

As during any transition period, a fierce battle seems to be underway between advocates of the two frameworks. This is weighing heavily on financial markets accustomed to central bank largesse. In fact, markets are suddenly rediscovering the concept of risk. More fundamentally, as argued in this memo, they are rediscovering a function that has almost been overlooked since the financial crisis: the valuation of economic risk.

A brief review of some key events over the past year is required: in January, the Swiss National Bank scrapped its currency floor with the euro. Virtually instantaneously, this decision triggered a spectacular bout of volatility. In August, the Chinese central bank successively devalued its currency resulting in a major stock market correction as well as a sharp fall in emerging market currencies. In September, when the first rate hike finally seemed just around the corner, the Fed referred to “global developments” when deciding to “temporarily” delay its decision. Lastly, in December, the Fed finally decided to break with its zero rate policy at the risk of slowing an economy weakened by those emerging market developments.

Some people will only see a series of disparate and staggered reactions behind these events. On the other hand, we see a process of normalization that, from our perspective, is becoming more and more pronounced. This is taking place at a time when it is increasingly apparent that the public policies implemented since the financial crisis are not having the expected effects. On the contrary, we think that the common denominator behind these events takes the shape of new systemic risks that the public policies are self-engineering. The ‘cost / benefits‘ ratio, to take a term employed by central bankers themselves as a control metric of their polices, has shown ongoing deterioration (note that the concept of ‘checks and balances’ works even better when it is independent and objective…). In the case of Switzerland, the sums required to maintain the floor had risen to unacceptable proportions, representing whole fractions of the country’s economic capacity. In the case of China, the mismatch between a fixed exchange rate system, weak economic growth and spectacular capital flows overcame the Yuan. In the case of the United States, it is our belief that this dramatic shift in the direction of emerging market flows had a major impact on the Fed’s monetary flexibility by interfering with domestic growth. In any event, the real capacity of the economies in question, or more specifically their weakness, came back to the fore.

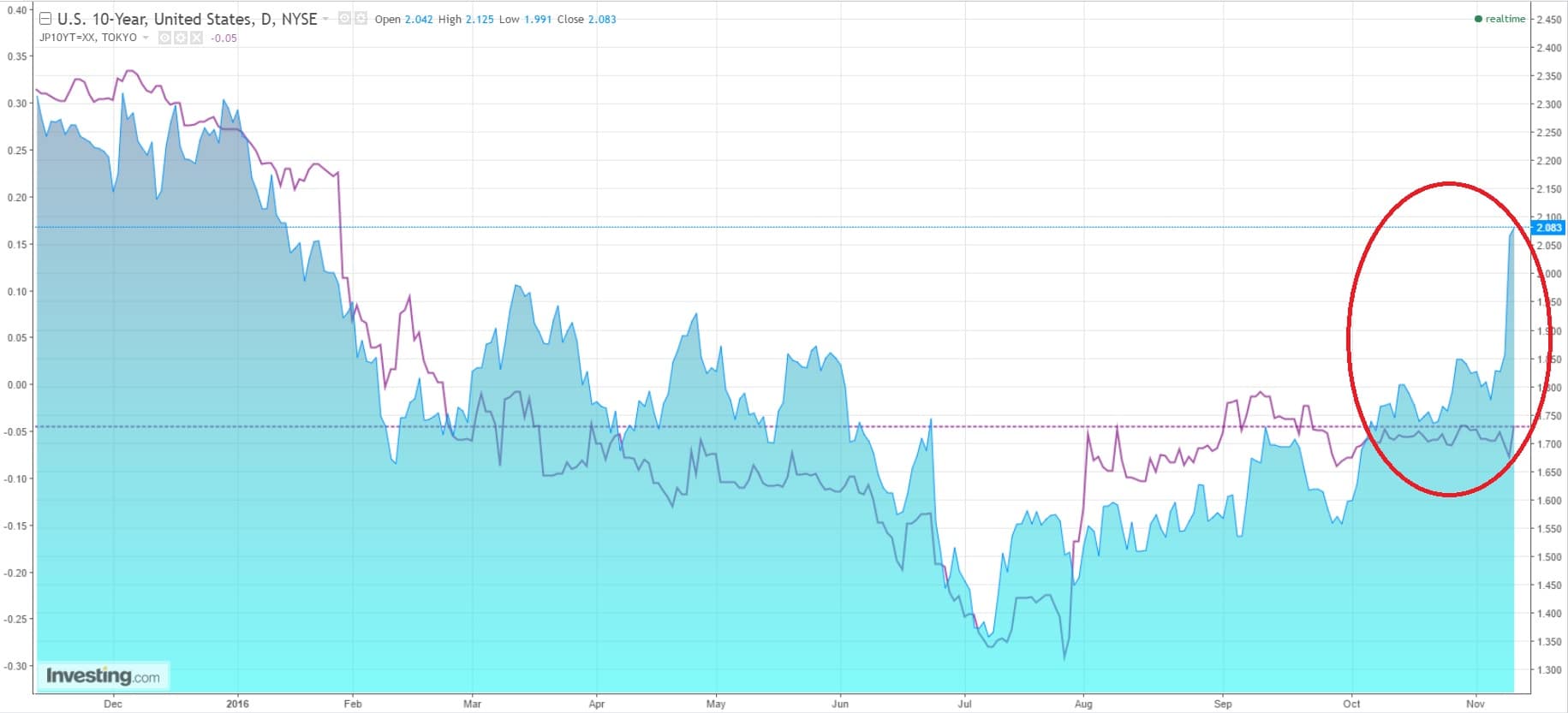

Central banks have received a reminder about systemic issues that is forcing them to reconsider the contours of their monetary policies. While markets are basing their hopes on further largesse from the European or indeed the Japanese central banks, we on the contrary expect to see a forced normalisation of their unconventional policies. As we said in the introduction, there are two opposing frameworks: the first monetary, decidedly public and interventionist, seeming guarantor of risk-free growth in financial assets under the reassuring watch of central banks, the other fundamental, obstinate, slow and powerful, that reflects the real underlying capacity of the economy.

In the corner opposite to ‘public policy divergences’, on which financial markets are basing their hopes, is ‘systemic convergence’, the main driver of which is none other than financial stability.

The impact of this trench warfare on the financial markets has risen over recent months, in the form of the SNB’s “Frankenshock”, the Chinese turmoil during the summer, the Fed’s decision in December or, going further back in time, the ‘taper tantrum’, the European sovereign debt crisis and of course the financial crisis.

Set against the excess debt, credit and easy capital that the markets love are economic penalties that they enjoy a lot less. Pushed to the extreme, these two approaches are sources of turbulence faithfully reflected by financial volatility.

Jacques Raemy