Negative interest rates

The risk-on mood has been powerful these days.

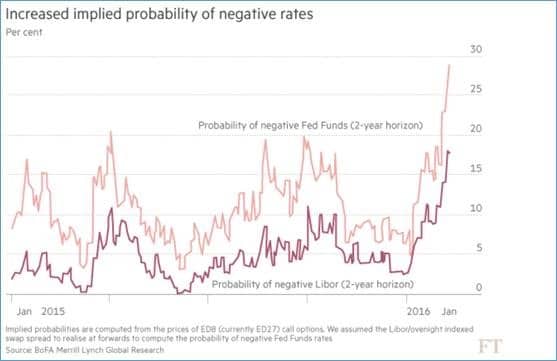

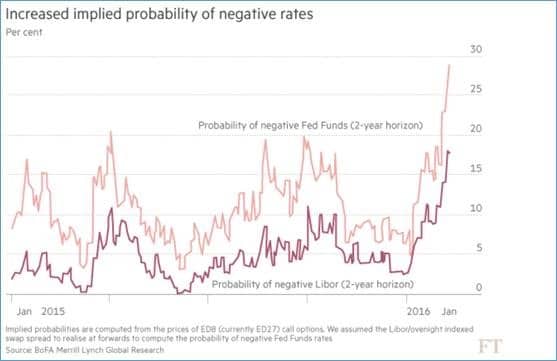

I stick to my recommendation of a cautionary stance with regards to the efficacy of policy intentions. The expectations of further interventions are indeed very high, a good example being negative interest rates (see below). At the same time their effects are increasingly challenged by the markets themselves.

The reason being: current policy options lead to poor or even counterproductive results.

The FT covers the issue in ‘Central banks, negative thinking’: (emphasis is ours)

Negative results

Sweden, Switzerland, Denmark, the eurozone and most recently Japan — adding up to almost a quarter of the global economy — have all introduced some form of negative interest rate policy in an attempt to fight deflationary forces, weaken their currencies and stimulate growth. Some analysts believe the Federal Reserve will have to follow suit despite its move to raise rates in December for the first time since 2006. Janet Yellen, the US central bank’s chair, has admitted that policymakers have at least considered the possibility.

Markets have generally applauded every central bank move to ease monetary policy since the financial crisis, but have grown anxious over the negative interest rate experiment. Some investors and analysts fear the moves are an alarming reflection of dwindling central banking firepower, and that the new weapon could even be dangerous.

“Policymakers may have significantly underestimated the economic risks,” Scott Mather, one of Pimco’s chief investment officers, said last week. “It seems that financial markets increasingly view these experimental moves as desperate and consequently damaging to financial and economic stability.”

|

Systemic impacts

Here we go: when easing policies fail to deliver, other forces must be at play. We nicknamed this phenomenon ‘systemic convergence’ as financial and economic stability may be at stake.

Stephen Roach also refers to financial (in)stability when assessing negative interest rates in the context of policy transmission.

Please consider ‘Central Banks go negative‘:

In the brave new era of unconventional monetary policy, the transmission channel runs mainly through wealth effects from asset markets.

Two serious complications have arisen from this approach. The first is that central banks have ignored the risks of financial instability. Drawing false comfort from low inflation, overly accommodative monetary policies have led to massive bubbles in asset and credit markets, resulting in major distortions in real economies. When the bubbles burst and pushed unbalanced economies into balance‑sheet recessions, inflation‑targeting central banks were already low on ammunition – taking them quickly into the murky realm of zero policy rates and the liquidity injections of quantitative easing.

Second, politicians, drawing false comfort from frothy asset markets, were less inclined to opt for fiscal stimulus – effectively closing off the only realistic escape route from a liquidity trap. Lacking fiscal stimulus, central bankers keep upping the ante by injecting more liquidity into bubble‑prone financial markets – failing to recognize that they are doing nothing more than “pushing on a string” as they did in the 1930s.

|

Let us reformulate our thesis of systemic convergence :

- What if, by continuously adding new layers to their unconventional policies – in this case negative interest rates – Central banks had self-engineered systemic cracks ?

- What if these fissures would lead to the exact opposite, counter-productive policy responses ?

We suggest: when systemic risks are at stake, central banks have no other choice but to let the markets find their way, otherwise they would perilously harm the economy.

Roach has a clear take about it:

The shift to negative interest rates is all the more problematic. Given persistent sluggish aggregate demand worldwide, a new set of risks is introduced by penalizing banks for not making new loans. This is the functional equivalent of promoting another surge of “zombie lending” – the uneconomic loans made to insolvent Japanese borrowers in the 1990s. Central banking, having lost its way, is in crisis. Can the world economy be far behind?

|

Jacques

Un blog sur la finance